Dr. Fanny Butler, among other women doctors, decided to make the long trek to India from Britain during the 19th century.

Traveling overseas during the 19th century was not for the faint of heart: disease frequently broke out on ships, killing many on board. It was so bad that people had believed that the ship itself became infected.

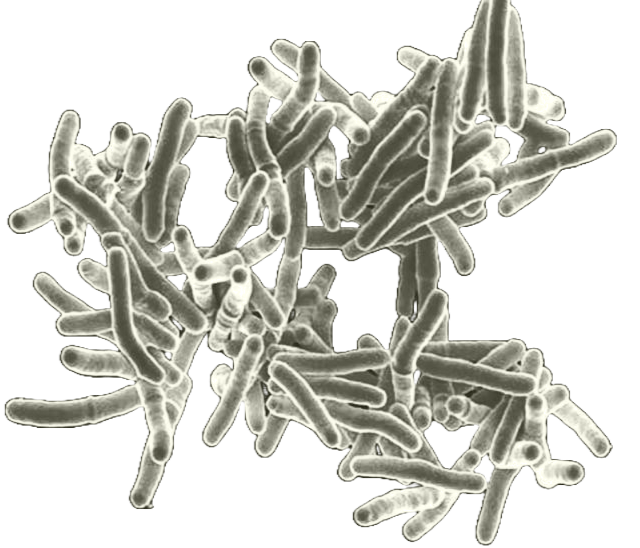

Upon arriving in India, these women physicians treated diseases such as tuberculosis and sought to convert Indian women to Christianity, building hospitals and dispensaries in the process.

This is the story of why some of the first women doctors in Britain took the arduous trek to India, what they did there, and how they contributed to treating tuberculosis in India and our understanding of tuberculosis in India during British rule.

From Britain to the Zenanas

How British Physicians Treated Tuberculosis in India

Initial attempts by the British in the early 1800s to convert Indian women to Christianity focused on reaching women through schooling. But, due to social customs prohibiting women from attending school, this approach was infeasible.1 The taboo against schooling for Indian women provided the British with a reason for conversion: they were trapped in a sexist society. In an article named “Hindu Female Education” published in The Calcutta Christian Observer, Priscilla Chapman articulated the importance of female education, stating, “the subject of female education occupies the greater attention… because of its intrinsic importance….” Her solution to the lack of female education was to preach the gospel, which, if missionaries didn’t, “[they] shall wait for ever [for female education].”2 This reason was echoed by missionaries at the time. But they had yet to find a replacement for schools by the 1840s, when the aforementioned edition of The Calcutta Christian Observer was released. Where could they convert the women? The zenana (a place in a Muslim, Sikh or Hindu house in India that is reserved for women) provided a solution to this problem.3

At the time, missionaries viewed zenanas as freedom depriving, secluded places. The women were inaccessible to male missionaries; they were, in the words of Julius Richter (a physician at the time), “banished to their zenanas.”4 To him, and other missionaries, the women were trapped in the zenana and needed spiritual and physical salvation.5 This line of thinking would form another reason to enter the zenana: they needed saving.

An early attempt to enter a zenana was in 1858 by John Fordyce’s wife.6 At the time, there were few female missionaries.7 The main reason for John Fordyce to choose women to enter the zenanas was because of Indian customs at the time. In the 1800s, women (mostly from upper castes) were culturally prohibited from seeing men from outside of their immediate family.8 This restriction prohibited male missionaries from entering the zenana, leaving the task to female missionaries. As Richter, a British physician, stated, “these zenanas are inaccessible for missionaries and native preachers all over India….”9 (By “missionaries and native preachers” he is only referring to male missionaries and male native preachers.) Later on in his book, Richter would conclude that “if men could not do this, it was agreed, here is an immense field open to women workers.”10 And they would fill that field; Fordyce’s wife would be the one of the first of many British women to enter a zenana in the late 1800s and early 1900s. And in the process, she helped open up missionary and physician work in India to the many women that would follow.11

This opening led to an increase in British women entering the zenanas in the latter half of the 1800s. According to Richter, by 1881, there were 479 female missionaries who had visited more than 9,000 zenanas.12 This number likely increased over the years as physicians and missionaries from Britain, the United States and other nations.

Dr. Fanny Butler was also an early British zenana missionary. Butler was a doctor and missionary born in Britain. In a sketch of Dr. Butler, E. M. Tonge described her as a very religious person growing up, writing “Fanny Butler did not wait until sailing for India to begin missionary work, but quietly used opportunities of leading students and patients to Christ.”13 Butler was also interested in medicine and was one of the first women to get her license in Britain. After getting her license, Butler sailed to India as a part of the Church of England Zenana Missionary Society, where she would spend the rest of her life.14

Dr. Butler was certainly not the last doctor to go to India. During the late 1800s, women in Britain started to enter medical school for the first time. Some of these women had started their careers in nursing15 (which was often one of the only jobs available to women in the medical field), but then entered medical school and eventually became doctors.16 But becoming a doctor in Britain, for many women, did not guarantee a job. Doctors who did not go looking outside of Britain for work “struggled to maintain a general practice….”17 This lack of jobs, mixed with other discrimination, put pressure on these female doctors to seek jobs elsewhere.

For some, India was an appealing option.18 Not only did India offer women job opportunities, the colonial state also provided them with new motivation and training. India was motivating to British women physicians who viewed Indian women as needing medical attention and “saving” from the aforementioned seclusion.19 Indian customs dictating who Indian women could see played a huge role in women not receiving the apparent medical attention they needed. Specifically, Indian women didn’t get medical attention because they were barred from seeing men outside the family, restricting medical attention to the small female-specific hospitals and dispensaries that existed at the time (although, that would increase with the increase in zenana missionaries).20 As the British Surgeon General Balfour wrote in 1872:

If a Mohammedan woman or Hindu of the higher castes be attacked with any severe disease, or have any bones injured, neither of them obtain the benefit of the knowledge which is at their doors, because it is only as yet in the possession of medical men, and men are not admissible into the women’s presence.21

These women in the zenanas still had access to Indian medical care, but many Westerners did not consider the care valid at the time. Many British saw the zenana as unsanitary, which reinforced the notion that the women needed rescuing from the unsanitary and freedom depriving zenana.

For many women, including, most likely, Dr. Butler, health was not the only motivating factor. Christianity was another motivating factor. As was mentioned before, Dr. Butler was reportedly very religious growing up and “did not wait until sailing for India to begin missionary work,” suggesting that religion was a motivating factor in her decision to go to India.22 These British doctors, as will be laid out later on, did not leave the opportunity to teach their patients about the Bible, including religious teachings at every chance, from dispensaries to the zenanas.

Colonial medicine during British rule was, with few exceptions like the zenana missionaries, restricted to Europeans.23 Tuberculosis (TB) was no exception. British colonialists did not understand how prevalent TB was in India (or, to be more specific, how prevalent the disease infected Indians). Some British colonists even believed that Indians were immune to TB.24 This lack of knowledge was largely due to the lack of colonial medical reach into Indian communities, which would begin to change as colonial rule changed.

The zenanas provided one of the only windows into the reality of TB in India for the British.25 One of the best examples is that of Arthur Lankester, a British researcher and missionary who, from July of 1914 to June of 1916, traveled across India gathering evidence to “stimulate inquiry regarding” tuberculosis in India.26 Lankester hoped that his finding would “lead to that spread of knowledge which is the successful preliminary to successful preventative effort.”27 One of the most important places he got his information from was missionaries—such as those visiting the zenanas. When addressing the question of where he gets his information in the first part of his book, Lankester stated, “I have tried whenever possible to obtain the opinions of civil surgeons, doctors of”Lady Dufferin” hospitals, private practitioners, medical missionaries, as well as of non-medical zenana workers, selecting always for special inquiry those who have remained in the same district for 20 or 30 years.” Lankester went on to explain how zenana missionaries hold the most valuable information.28 Many of those “doctors of ‘Lady Dufferin hospitals’” were zenana missionaries too. As will be discussed later on, these zenana missionaries often opened and staffed hospitals specifically for women, such as those funded by the Dufferin fund (instantiated by Lady Dufferin), which is likely what “‘Lady Dufferin’ hospitals” is referring to.

According to Lankester, during the early 1900s, TB was spreading rapidly throughout India, specifically into rural areas “where formerly it [tuberculosis] was almost unknown.”29 He mainly attributed the rise of TB to two things: British rule and the zenanas. British raj caused overcrowding and forced people into enclosed spaces, which caused the increase in TB.30 The zenanas were “enclosed”, Lankester reasoned, causing them to become unsanitary and cause TB.31 It is important to note that enclosures causing TB was not an uncommon idea during that time, the main point of contention being whether unsanitary/enclosed spaces could be fixed or not.32 Lankester was among the ones that believed they could be fixed.

Shortly after after Dr. Butler arrived in India, she joined the Zenana Mission House, a dispensary in Bhagalpur.33 For the next four and a half years, she stayed at the dispensary, treating the few patients that they got.34 Dr. Butler staffing a dispensary was not uncommon. Many women doctors from Britain would open women dispensaries and hospitals that provided treatments ranging from tuberculcilin shots to “open air” treatment.35

In his sketch of Dr. Butler, E. M. Tonge recounted a story of Dr. Butler treating a woman in a zenana: some time during those four years at the dispensary, she received a telegram from a Maharani’s manager (the wife of a Maharaja, a prince). After going on a 12-hour journey and arriving at the Maharani’s house, she was sent back home because the Maharani didn’t want to see an Englishwomen.36 This rejection shows how, even after the zenana missionaries started to enter the zenana, they were not always accepted by the Indian women.

The Maharani’s manager eventually telegrammed Dr. Butler after three weeks. This time, the Maharani would accept Dr. Butler’s care. The Maharani was likely in a zenana. “The Maharani was behind a red curtain in the one large room of a poor little house,” he wrote.37 The zenana was also busy, there were “some 300 servants and retainers were about the place,” presumably to treat the Maharani.38 Once admitted into the zenana, Dr. Butler saw “a young women, very thin and ill, and with a discontented expression, lying on a silver-legged bed. She was wearing a common kurta and sari, glass bangles and a bead necklace.”39 The Maharani was suffering from TB, which had likely caused her to become “very thin” and have a “discontented expression.” But this is not what Dr. Butler attributed her state to. Instead, she placed the blame on the native healers who had treated the Maharani before Dr. Butler was called, stating, according to Tonge, “the invalid, who was suffering from consumption, had been treated by many quacks, and as a result had been nearly starved.”40 Dr. Butler’s reaction to the Maharani’s state reveals the missionaries’ view of native doctors: an unfavorable one at best or a malicious one at worst. The sketch also mentioned what Dr. Butler found unfavorable about the treatment: “fresh air had been considered dangerous, and for five months she [the Maharani] had not been allowed to touch her body with water, though she was occasionally oiled.”41 While this could be read as the author of this sketch giving a commentary on what Dr. Butler thought was dangerous, Tonge is really talking about what the native doctors thought was dangerous considering the second half of the sentence: “for five months she had not been allowed to touch her body with water”. It is also clear that Dr. Butler had not banned the Maharani from touching her body with water as Dr. Butler had not been at the Maharani’s house for five months. Native doctors keeping the Maharani enclosed (or not allowing her to see “fresh air”) went directly against the British understanding of TB in India. British colonists believed that the disease was caused from being enclosed in an unsanitary place with little air flow or sun access. From this view, the Maharani was kept in the very place that was causing her illness!

According to the sketch, the Maharani approved of Dr. Butler’s treatment and wanted Dr. Butler to visit her two or three times a day. But Dr. Butler could not agree to this as she would have to close the dispensary while treating the Maharani. She left a few days after arriving, notably “not before she had been able to give [the Maharani], and her little girls some Bible teachings.”42 A few months later, “Dr. Butler was grieved to see a notice of [the Maharani’s] death.” According to Tonge, Dr. Butler blamed the death on Indian doctors, concluding that the Maharani “probably soon returned to quack treatment.”43 Further reinforcing her view on Indian doctors.

With all that these women did, from taking the long trek from Britain to India to treating TB in the zenanas, I struggled to find any Indian perspectives. That is likely due to a language barrier, but if you have any books, articles or even knowledge pertaining to any of the issues mentioned above, please send them to me at [email protected], I will be very grateful!

Footnotes and citations

1: Richter, A History of Missions in India, 331.

2: Christian Ministers of Various Denominations, The Calcutta Christian Observer, 1:117–18. Given that missionaries in India first tried to reach women through schools, this lack of female education also made it hard for missionaries to reach women, giving them another reason to push for more female education through the gospel. This may have been push through males at first, because, at the time, one idea to reach women was through their husbands, who would, in theory, be so intolerant of their “wives who were holly illiterate” to open up their homes to missionaries. (Richter, A History of Missions in India, 332)

3: Khan, Purdah and Polygamy, 68.

4: Richter, A History of Missions in India, 329.

5: Venkat, At the Limits of Cure, 45.

6: Richter, A History of Missions in India, 338. Sadly none of the texts mention her name.

7: Antoinette Burton, “Contesting the Zenana,” 371. This sexism is evident by the apparent pushback from male missionaries on women entering the field. (Richter, A History of Missions in India, 339) Also, it is very ironic that male missionaries put themselves on the moral high ground for “saving” the women from the culture while they were sexist in their own right.

8: Richter, A History of Missions in India, 329; Lal, “The Politics of Gender and Medicine in Colonial India,” 40.

9: Richter, A History of Missions in India, 329.

10: Richter, 331.

11: Another barrier to entering the zenana, according to the missionaries at the time, was the husbands of Indian women not being familiar with Western culture. Once converted, the men would have “become so far familiar with Western culture as to be able no longer to tolerate wives who were holly illiterate [to Western culture]” and consequently let the missionaries into their house. (Richter, 337)

12: Richter, 341.

13: Tonge, Fanny Jane Butler, Pioneer Medical Missionary, 13.

14: Tonge, 14.

15: Heggie, “Women Doctors and Lady Nurses,” 268. Women’s establishment in nursing (and thus the hospital) also provided a counterargument to arguments that women shouldn’t be in the hospital. (Heggie, 268)

16: Heggie, 267.

17: Heggie, 291.

18: It was not unusual for Christian missionaries to also be trained in medicine. (Richter, A History of Missions in India, 346)

19: Antoinette Burton, “Contesting the Zenana,” 369.

20: Richter, A History of Missions in India, 329.

21: Martindale, The Woman Doctor and Her Future, 103.

22: Tonge, Fanny Jane Butler, Pioneer Medical Missionary, 13.

23: Venkat, At the Limits of Cure, 56–57.

24: Venkat, “Untimely Morbidities,” 18.

25: Venkat, 13.

26: Lankester, Tuberculosis in India, viiii.

27: Lankester, viii. Sadly his finding would never lead to successful preventative efforts. In 1916, he submitted his findings to the colonial government but was never released to the public, leading him to publish his findings in a book in 1920. (Venkat, At the Limits of Cure, 47) As Venkat outlined, “he received mixed reviews: some agreed that TB was a serious problem for the health of the Indian population, and others insisted that his findings were overblown.” (Venkat, At the Limits of Cure, 47) In 2023, in India alone, over 300,000 people died of TB, with over 2.8 million being infected. (World Health Organization, “Tuberculosis Profile”) It is not hard to say that TB hasn’t been eliminated in India.

28: Lankester, Tuberculosis in India, 14.

29: Lankester, 10, 11.

30: Lankester, 32–33.

31: Lankester, 140, 141.

32: Arnold, Colonizing the Body, 32.

33: Tonge, Fanny Jane Butler, Pioneer Medical Missionary, 18.

34: Tonge, 19; Lankester, Tuberculosis in India, 232.

35: Richter, A History of Missions in India, 450; Lankester, Tuberculosis in India, 230–31, 233.

36: Tonge, Fanny Jane Butler, Pioneer Medical Missionary, 26.

37: Tonge, 26.

38: Tonge, 26.

39: Tonge, 27.

40: Tonge, 27.

41: Tonge, 27.

42: Tonge, 28.

43: Tonge, 28.

Antoinette Burton. “Contesting the Zenana: The Mission to Make ‘Lady Doctors for India,’ 1874–1885.” Journal of British Studies 35, no. 3 (July 1996): 368–97. .org/10.1086/386112).

Arnold, David. Colonizing the Body: State Medicine and Epidemic Disease in Nineteenth-Century India. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1993.

Bala, Poonam. Contesting Colonial Authority: Medicine and Indigenous Responses in Nineteenth- and Twentieth-Century India. Lexington Books, 2012.

Christian Ministers of Various Denominations, ed. The Calcutta Christian Observer. Vol. 1. Calcutta, 1840. http://archive.org/details/calcuttachristia01unse.

Heggie, Vanessa. “Women Doctors and Lady Nurses: Class, Education, and the Professional Victorian Woman.” Bulletin of the History of Medicine 89, no. 2 (2015): 267–92. https://muse.jhu.edu/pub/1/article/584753.

Khan, Mazhar-ul-Haq. Purdah and Polygamy: A Study in the Social Pathology of the Muslim Society. Nashiran-e-Ilm-o-Taraqiyet, 1972. https://books.google.com?id=wm1FUxqngwAC.

Lal, Maneesha. “The Politics of Gender and Medicine in Colonial India: The Countess of Dufferin’s Fund, 1885-1888.” Bulletin of the History of Medicine 68, no. 1 (1994): 29–66. https://www.jstor.org/stable/44451545.

Lankester, Arthur. Tuberculosis in India: Its Prevalence, Causation and Prevention. Butterworth, 1920. https://books.google.com/books?id=P0s2AAAAIAAJ.

Martindale, Louisa. The Woman Doctor and Her Future. Mills & Boon, limited, 1922. https://books.google.com?id=lRu6AAAAIAAJ.

Richter, Julius. A History of Missions in India. Creative Media Partners, LLC, 1908. https://books.google.com?id=SbgtvQEACAAJ.

Tonge, E. M. Fanny Jane Butler, Pioneer Medical Missionary. London: Church of England, Zenana Missionary Society, 1939.

Venkat, Bharat Jayram. “Untimely Morbidities: Tuberculosis, HIV, India,” 2014.

———. At the Limits of Cure. Critical Global Health: Evidence, Efficacy, Ethnography. Durham: Duke University Press, 2021.

World Health Organization. “Tuberculosis Profile: India,” November 28, 2024. https://worldhealthorg.shinyapps.io/tb_profiles/....